I ordered a book of poems by Paul Zweig, because poetry is the muse to my fiction, because it pertains to the novel I’m currently working on, and because I have a peculiar connection to Paul Zweig.

I met my first wife in 1984, a young French woman staying at a friend’s apartment whom I happened to espy at the Hungarian Pastry Shop, a smoky mainstay of Columbia student life for the past 60-plus years that features bottomless mugs of coffee, dry-but-tasty pastries, uncomfortable wooden chairs, the annoying conversation of philosophy majors, and the constant distraction of attractive young people of every gender imaginable.

It turned out that Anne was staying at Paul Zweig’s Morningside Heights apartment, which he shared with his wife and lived in during terms when he had a gig teaching at Columbia University’s School of the Arts; otherwise, he spent most of his time at his country home in France, or at a borrowed apartment in Paris.

But the Morningside Heights apartment wasn’t the only connection we had – nor was the fact that I was earning my MFA at Columbia at the time, and that Paul and I had crossed paths there without ever formally meeting, because Paul was close friends with my thesis advisor (and department head) Robert Towers.

Paul had a ramshackle home in the Perigord region, a lush stronghold of truffles and traditional cuisine located just far enough into the French hinterlands to be inexpensive enough for a poet and adjunct professor to afford. The house was next door to a lovely couple of retirees who quickly befriended their odd, studious, Francophile American poet neighbor.

They loved to cook traditional French fare, and he loved to eat it – and so a friendship was born. They had kept their Parisian apartment so they could return from time to time to go to the theater or to visit friends, and so their granddaughters could also have a place in Paris. They let Paul stay there whenever he needed to be in Paris.

One of those granddaughters was Anne, and after we had met and fallen in love, she returned to that Paris apartment to continue her studies (she had earned her license, the equivalent of a BA-plus, and was going for her maitrise, or master’s).

Just after her return, Paul, who was staying in one of the rooms in the apartment, collapsed in the staircase and died. Not yet 50, Paul succumbed to cancer, almost, she sobbed to me over the phone, in her arms.

It’s quite possible that Anne saw in me, a New York-born Francophile Jewish writer with a prominent nose, something of a Paul Zweig. In any case, Anne came to stay with me that fall, and we married the next spring. Professor Towers, who knew Anne and her family through Paul, allowed me to leave school early (once I had finished my dissertation, soon to become my first published collection of short stories) so I could be with my new bride as she pursued her degree.

Anne and I were married for three years; I remained in France for another 9 years before returning to the US. The Hungarian Pastry Shop is still in business. And I’m working on a novel set in the Paris of 1989. It set me to thinking about Paul’s work, and especially a line of his about the Seine’s “muscular waters” – a description so apt that it has stuck in my mind all these years, even though I can’t remember the specific poem.

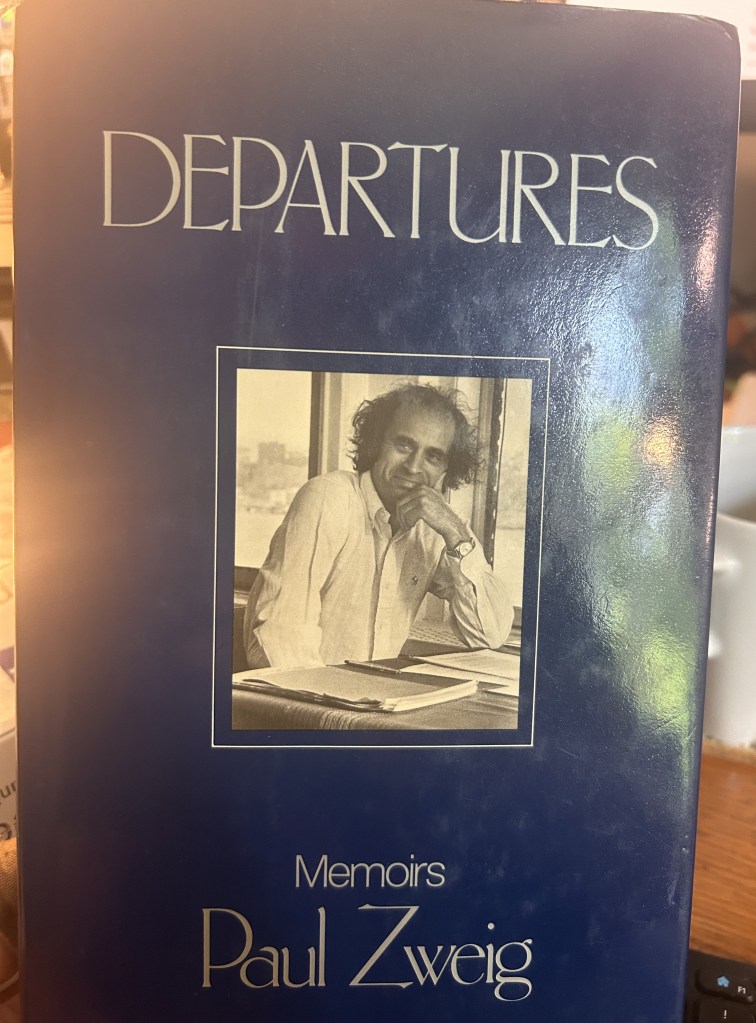

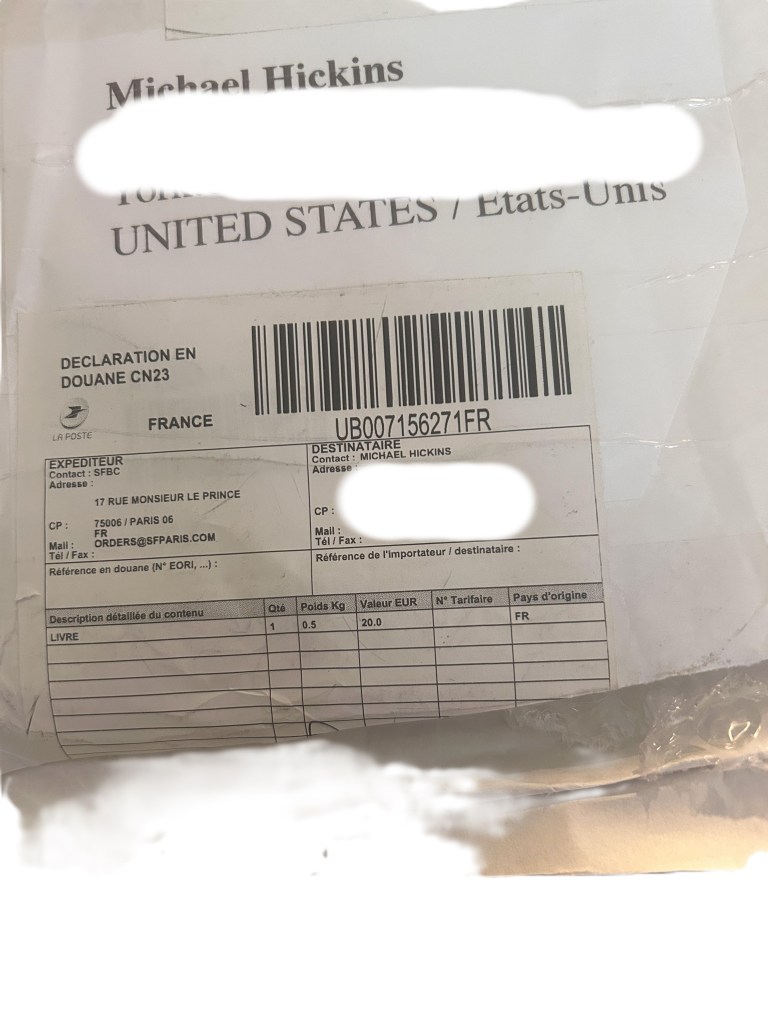

So I ordered a couple of his books, hoping to come across the line. And one by one the books arrived from this online shop and that one. One of those, a memoir entitled Departures, came all the way across the Atlantic, from a bookstore in Paris called, of all things, San Francisco Book Co.

And so I’m in New York, researching a book about Paris and reading a book by a fellow New Yorker with whom I crossed paths some 40 years ago, whose neighbor’s granddaughter I married, and which has been sold to me by an American bookstore in Paris.

If life isn’t circuitous, curious, and quizzical of cast, I don’t know what is!