As asylum-seekers drown in the Rio Grande under the indifferent eyes of the Texas National Guard, and as Donald Trump celebrates his primary victory in Iowa this week, Jews especially should take heed of language such as poisoned blood and vermin used when discussing immigration.

Trump has promised that if elected, he will strip citizenship from people born in the US of immigrant parents – even Nikki Haley, his rival for the GOP nomination, is a target of this jeremiad, as he rails that she is unqualified for office because her parents were immigrants.

I’ve been reviewing documents that provide a record of my father’s arrest in Belgium during WWII, his interment in a refugee camp, his rescue by the mayor of Meillon, a small town in southwest France, and his eventual immigration to Cuba.

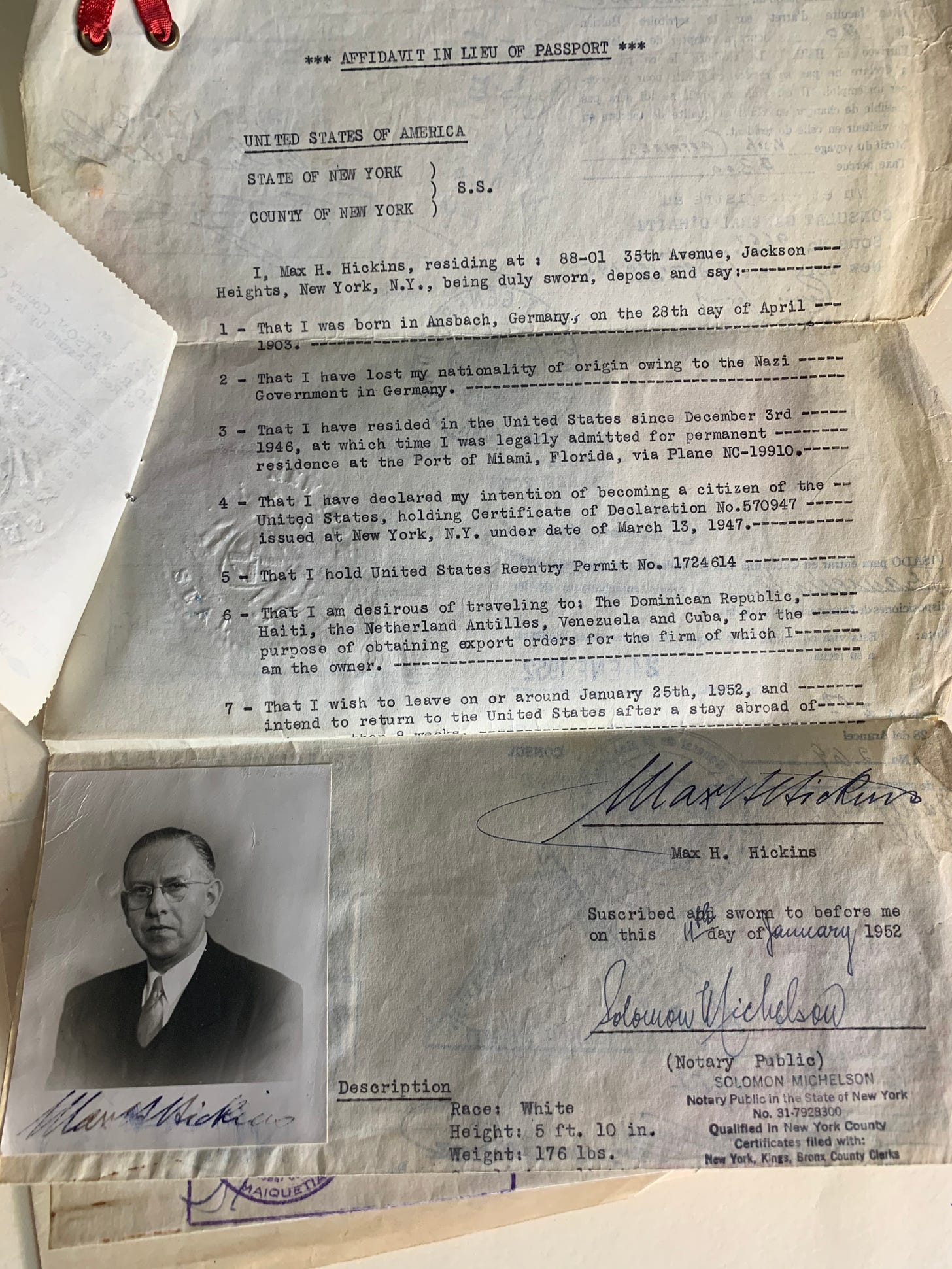

The image embedded in this post is of a letter from the Cuban embassy informing my father that he and his wife and infant son had been granted a visa to Cuba.

In an age of instant communications, it’s impossible for us to imagine the anticipation, the dread, the hope, that accompanied the arrival, after months of waiting, of this letter.

Addressed to my father, Max Hirschkind, in care of the Mayor of Meillon, Paul Mirat, at whose house he was then living, it reads:

Marseille, September 13, 1941

Dear Sir,

We have just received a telegram from our Department of Foreign Affairs giving us the authorization to provide you, along with your wife Mrs. Hildegard Hirschkind and your son Walter Hugo Hirschkind, visas allowing you to travel to Cuba.

All three of you should come to our office either Friday the 19th of the present month or the following Monday, along with your passports or French safe passages (travel authorizations) in order to receive your visas and, at the same time, submit to a health inspection performed by the doctor assigned to the consulate.

Best regards,

(signed)

The Cuban Consul

Note that the consul asks my father to bring the family’s safe passage documents – these were in lieu of passports, which my father and his wife and son didn’t have. It bears repeating that they didn’t have passports because they were German Jews, and Germany had in 1936 stripped Jews of their nationality.

This was not merely an insult and a nasty bureaucratic formality – he couldn’t freely travel abroad, and had no homeland, no place to call home. Many German Jews committed suicide from despair of this.

The health inspection referenced by the consul was no mere formality – Walter’s tuberculosis had prevented the family from emigrating to the United States. Although now healthy, the prospect of awaiting the outcome of this inspection must have been quite daunting.

Note also that the letter was addressed to my father care of Paul Mirat. I’ve described how the mayor of Meillon managed to get thousands of internees out of the camps and into the homes of Meillon residents – including his own home. According to his grandson, Mirat and his wife actually rented out another smaller apartment in town for themselves so that they could give their whole house over to prisoners (such as my father) who had families.

Purchase my memoir, The Silk Factory

Others lived in the stables out back, on small metal cots, and were provided lamps and a few other necessities.

Today, as we contemplate a war-torn world that seems ready to fall back upon itself in timid isolationism, we should be inspired by the example of Meillon, a town of 600 people who took in thousands of refugees to spare them the indignity of living in a filthy camp, to spare them the separation from their loved ones, and ultimately to spare them their lives.

[Please consider purchasing my memoir, The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family’s True Holocaust Story (Amsterdam Publishers, 2023)]