We all come to Yom Hashoah — Holocaust Remembrance Day – by different paths.

For me, it’s an ongoing education into my family’s history, which I detail in my memoir, The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family’s True Holocaust Story.

And this year in particular, Yom Hashoah was jolted into my consciousness by a photo someone shared on Facebook of a group of Jewish students celebrating a Passover Seder while occupying the Columbia University campus in protest of the war in Gaza.

It wasn’t the photo itself that brought me back to the Holocaust, but rather a Facebook comment caviling about “gentrifiers protesting gentrification 6,000 miles away.”

That takes a little bit of unpacking. What the photo showed was a subset of protestors, ostensibly Jewish students, observing one of the most important holidays of the Jewish calendar, while also protesting what they see as an unjust war and, probably, the commission of war crimes.

However, what the commenter saw was a bunch of greedy Jews who are just as illicitly occupying Brownsville and Washington Heights as they are the West Bank. (Never mind that Jews have lived in Washington Heights for the past hundred years or so.)

But what the commenter also saw was: Jews = Israel = illegitimate.

In this view, Jews historically enjoy unjustified, immoral, and ill-gotten ownership over land, goods, and social status; they leverage this illegitimately achieved status to influence world politics, impose economic conditions on others, and create a moral hegemony that perpetuates their hidden power.

My personal education in Holocaust history began with a simple search in my basement for a photograph of my late half-brother Johnny. What I discovered during that search led me to learn a lot about my own family’s history, about just how close we came to being annihilated (and how close I came to not existing), and how the trauma that affected my family in the 1930s and 40s has affected my own psyche and impacted the development of my children.

What I also learned is that most people don’t think that kind of thing will happen again, or at least not here. There are other places where antisemitism is more prevalent, more vocalized, more acceptable. But the reality is that it doesn’t take a lot for this kind of thing to happen. It just needs to be allowed to fester and germinate and expand.

What is extraordinary is when people push do revolt against antisemitism.

Paul Mirat, the mayor of Meillon, a small town in France close to one of the refugee camps where my father was sent, made it so that my father – and thousands of other refugees (mostly Jews) – could live outside the camp, away from the dysentery and typhus that killed so many, to apply for visas, and to save themselves.

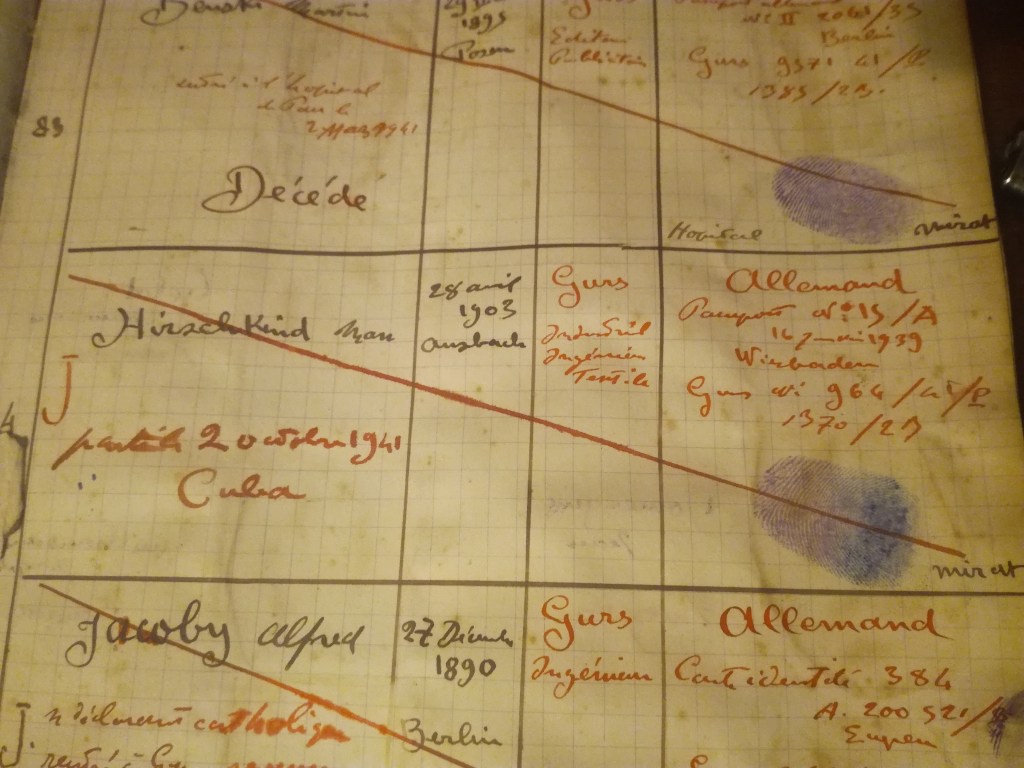

The photo above is a picture I took of the register kept by Paul Mirat, which lists my father – his name was Max Hirschkind (he subsequently changed it to Hickins) – and includes his date of birth, his profession (textile manufacturer – a silk factory), the name of the internment camp to which he had been assigned, and his thumbprint for purposes of identification.

There is a red J next to his name – for Juif (Jew in French).

Also noted was the date of his departure for Cuba – October 2, 1941. It was late getting out, and he was fortunate. In many ways.

The United Nations has proclaimed January 27 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day, choosing that date because that is the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and Birkenau.

In Israel as well as here in the US, Holocaust Remembrance Day is celebrated on the 27th day of Nisan on the Hebrew calendar – which this year corresponds to May 6. The 27th day of Nisan is the anniversary of the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, when some 700 Jewish fighters rose up against the Nazis in Poland. They were slaughtered, of course, and many thousands were then quickly murdered as well, in retaliation for the revolt.

What do you commemorate? The date on which the international community finally put an end to the Nazi death machinery? Or the anniversary of a Quixotic attempt at self-defense?

Many of us choose the latter, because although it failed, the uprising served as a symbolic act of defiance, and it alerted the world – if alerting was needed – that a monstrosity was growing in its midst.

Today, many Jews (myself included) are dismayed at the behavior of the State of Israel, and aren’t shy about expressing our position. But it’s also alarming to see that monster antisemitism growing around us, expressing itself under cover of anti-Israeli politics.

The true meaning of Yom Hashoah isn’t only that we must remember the Holocaust; it is that we should engage with the Shoah, discuss it openly with those closest to us, to ensure that it doesn’t happen again, to us, or to anyone else.

Genocide occurs when people objectify others, label them as not deserving of life, and act on that false premise. We have to be vigilant to identify those three characteristics – objectification of any group of people; denying a group of people their humanity; killing people based on a label – and to object to those characteristics immediately, vociferously, relentlessly. That is the lesson of Yom Hashoah for me.